Nurses Are Being Considered Easy Targets for Lawsuits

SALT LAKE CITY – Frontline health care workers have been treating patients under extraordinary conditions: overcrowded ICUs, staffing shortages and intense burnout.

While they have shouldered some of the highest risk during the COVID-19 pandemic, those exhausted physicians now find themselves with little protection from being sued for medical malpractice.

"This is a war zone," said Teneille Brown, a law professor at the University of Utah. "And when you are providing medical care in what is really the equivalent of a war zone, you cannot expect that care to be what it was before."

Fighting an Invisible Enemy

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, doctors and nurses working in intensive care units were battling an invisible enemy, without a sure weapon or a proper shield.

"I was terrified," said Brown, recalling how her husband, a doctor, traveled from Utah to New York to volunteer in 2020, where he donned trash bags as personal protective equipment.

"He's one of those people that runs towards danger when the rest of us run away from it," she said, describing Dr. Chak Reddy, an intensivist.

Dr. Chak Reddy has been treating COVID-19 patients in New York and Utah since the beginning of the pandemic.

It was a much riskier time, Brown explained, as there was not yet a vaccine.

Now, a year and a half later, despite the availability of three safe, effective, and free vaccines, hospitals are overwhelmed as COVID-19 cases continue to surge.

Monday, the Utah Department of Health reported the ICUs at Utah's 16 referral center hospitals, where most COVID-19 patients are treated, are 92.8% full. UDOH also reported that over the weekend, 23 more Utahns died due to COVID-19.

"The risk now is that he's not giving the care that he knows he needs to be giving," Brown said, explaining patients are coming in less frequently and missing routine screenings.

Looming Liability?

Brown doesn't worry about her husband contracting COVID from sick patients anymore, but as an attorney and law professor at University of Utah, she does anticipate an uptick in legal battles related to the virus.

"You make mistakes when you're tired, you make mistakes when you're stressed, you make mistakes when you're being asked to do things with fewer resources," Brown said. "When mistakes are made, and they're inevitably made, people are angry, and people want to place that blame somewhere."

Doctors and nurses on the frontlines of the pandemic are working to protect all of us, but do Utah laws do enough to protect them?

COVID Caregivers: Looming Liability airs tonight at 10 on @KSL5TV #KSL #KSLInvestigates pic.twitter.com/9uHeZmO4M4

— Daniella Rivera (@RiveraDanie) September 28, 2021

In the wake of a public health crisis, there's plenty of blame to go around, Brown said, but several groups will enjoy broad legal immunity.

"[People] can't place that blame on the doorstep of the government because the government's immune," Brown explained. "They can't place that blame on the doorstep of businesses who've been reckless because we've passed immunity laws that protect businesses from being liable for transmission of COVID. And so, there aren't very many people who are left standing who can actually be accountable for these mistakes."

While some might turn their ire toward members of the population who are unvaccinated and now account for the majority of COVID patients requiring hospitalization, they cannot be sued either, according to Brown.

"Even if they were a cause of this crisis, they're not a close enough cause to be found negligent for a negligence lawsuit," she said.

Brown worries doctors and nurses will become the targets of anger and blame by default.

"The one group who has no immunity and who could be sued are physicians and healthcare providers who are doing what they're doing because it's their job," said Brown.

Brown predicts there will be an uptick in medical malpractice and negligence claims filed related to reduced access to healthcare resources and treatment, emergency policies adopted by healthcare institutions and even potential mistakes made at the bedside amid the chaos of the ongoing public health crisis.

"Bullseyes on the backs of doctors"

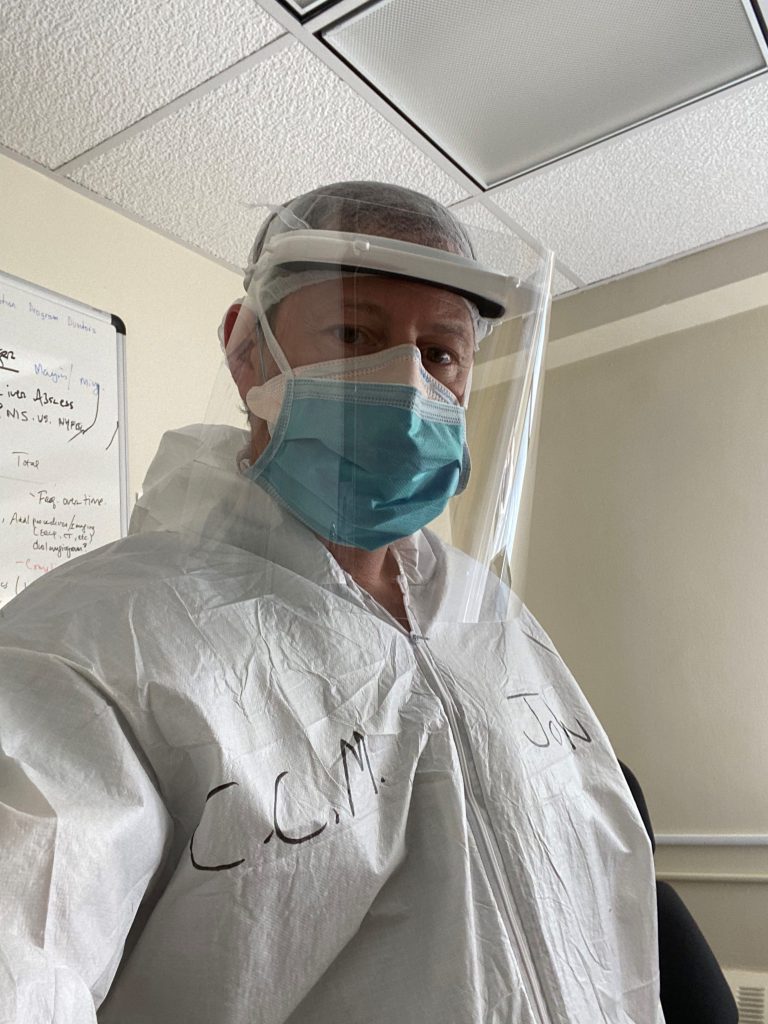

"It has been a very challenging environment to work in," said Dr. Jon Boltax, a pulmonologist at University of Utah Health on the COVID-19 frontline.

Boltax said medical professionals understand the possibility of being sued comes with the territory – even outside of a pandemic – but it's not something he lets himself think about while he's treating patients.

"We have worked very hard to care for people during the pandemic," Boltax said. "And we continue to do that, and we will continue to do that, and there is some personal sacrifice in doing that, and it would obviously be upsetting if we were, you know, then sued at the end of this."

Dr. Jon Boltax volunteered to treat patients in New York City during the early days of the COVD-19 pandemic.

According to Brown, medical malpractice and negligence suits often name anyone and everyone who laid eyes on the patient.

She said hospitals are insulated by insurance policies that typically cover the nurses too, but physicians can be sued individually.

"I think there are huge bullseyes on the backs of doctors," said Brown.

Utah Sen. Kirk Cullimore, R-Sandy, who is also an attorney, said he does not expect a rash of medical malpractice lawsuits related to the pandemic.

"I think it's going to be difficult to win on that type of a claim against a medical professional that's doing their best to treat COVID patients or any other patients," said Cullimore.

Cullimore sponsored SB 3007, the law that now protects businesses in Utah from being held liable for the transmission of COVID-19.

When it comes to the question of whether immunity should be extended to medical professionals, Cullimore said he trusts the courts to toss out lawsuits that are based on circumstances health care workers can't control.

"Those are factual things that will be considered in any type of a lawsuit," said Cullimore. "If the treatment or the care that a patient received was a little bit less, because the staff is… they're understaffed, or they don't have the supplies that they need, or the drugs that they need, then that all comes into play, and that's not going to be held against the medical professionals."

In the event of a medical malpractice claim, Cullimore and Brown both said the courts will judge the alleged actions, taken or not taken, against a standard of care and determine whether the medical professional acted reasonably under the circumstances.

"Anybody with a couple hundred bucks can go down and file whatever claim they want, right? And we deal with that pretty frequently," said Cullimore. "But it's going to be pretty easy to overcome … they're going to be able to demonstrate that they were doing the best that they can."

Even if the physicians win – which Brown said is usually the case – doctors still have to hire an attorney, show up to a deposition and defend their decisions.

"A physician could still be sued because their institution might have a policy that says, 'You know what, we're not doing any more of these kinds of procedures because we just don't have enough ventilators.' And a patient might be upset by that, might actually be injured by that, and they sue the physician, and there's nothing that kicks that out of court right away," Brown said.

And Brown said all malpractice lawsuits – even those thrown out – follow medical professionals throughout their careers.

"Every time you apply for privileges at a hospital, you have to list the times you've been sued," she said. "And even if the result is dismissed, right, there's still that ping of, you know, 'My professional judgment was called into question.'"

KSL Investigative reporter Daniella Rivera speaks with Teneille Brown, a law professor at University of Utah who anticipates an uptick in medical malpractice suits related to COVID-19.

While Brown and Cullimore predict plaintiffs bringing lawsuits over issues influenced or aided by the pandemic aren't likely to be successful, they also acknowledge that reality leaves patients and families who do receive a lower level of care due to the pandemic without many options for recourse.

"If a medical professional provided you the best care that they could, and, you know, bad things happen still, unfortunately sometimes that's life," said Cullimore.

Brown said patients aren't likely to see a big pay day and medical professionals still have to live with the risk of being sued – a situation in which no one is winning.

Politics and Blame

"It's because of failed political leadership," she said. "I place blame completely on the doorstep of politicians who took what was a public health crisis and made it a political one."

Brown believes the conditions medical professionals are working in could have been prevented had elected officials and government leaders done more to slow community spread of the coronavirus, including mandating masks in schools statewide.

Cullimore disagrees, saying lawmakers have to consider more than just the public's health when making decisions.

"By all metrics, Utah has done very well in addressing this pandemic, both from health perspective as well as the economic perspective," he said. "And as policymakers, that's what we have to do. I mean, if we drove policy, just based on health, then you would probably see a lot more mandates, a lot more restrictions."

A battle over politics and blame isn't something doctors want to be caught up in.

"People are dying that don't have to die," said Boltax.

He faults the incredible amount of misinformation that is spreading online and through communities.

Nearly every COVID patient he sees in the ICU is unvaccinated.

"We don't see how this is coming to an end any time soon," said Boltax. "And we feel that there's a chance that if everybody got vaccinated, we could get out of this pandemic."

Like Boltax, Brown said her husband, Dr. Reddy, is not worried about being sued.

But for those who are, Brown said the state could relieve the psychological impacts of the threat of a lawsuit by enacting a targeted immunity law.

"I think that if a physician is following a hospital policy about who they need to be triaging and giving the ventilator to, or the ICU bed to, I think that there should be immunity for those physicians, where it doesn't get to the level of being deposed and having to defend the lawsuit," Brown said. "It is just, you follow the institutional policy – no liability."

At the federal level, there have been multiple bipartisan attempts to secure better liability protection for medical professionals.

In May 2020, Tennessee Republican Rep. David Roe and California Democrat Rep. Lou Correa introduced H. R. 7059, the Coronavirus Provider Protection Act.

"The COVID-19 pandemic upended health care delivery across the country," Roe was quoted saying in a news release when the bill was first introduced. "Health care providers have gone above and beyond to meet whatever challenges they've faced, but now, we owe it to them to ensure they are protected from frivolous litigation."

In May 2021, Correa partnered with Texas Republican Rep. Michael Burgess to introduce H.R. 3021, also called the Coronavirus Provider Protection Act – a bill with the same objective.

Both measures appear to have stalled after introduction.

In Utah, the window to file a medical malpractice suit is two years.

Brown said it takes time to find an attorney and allow them to investigate the merits of a claim.

She expects to see claims pick up in the next six months to a year.

"If you make a mistake, and you do something that is unreasonable, I think you should have to pay for that and patients should be compensated for that, their family members should be compensated for that," said Brown. "It's all about figuring out what's unreasonable in this circumstance, when we're dealing with a pandemic and we're dealing with physicians who are incredibly under resourced."

Have you experienced something you think just isn't right? The KSL Investigators want to help. Submit your tip at investigates@ksl.com or 385-707-6153 so we can get working for you.

Source: https://ksltv.com/473427/looming-liability-doctors-nurses-on-the-pandemic-frontlines-are-likely-legal-targets/